Dangerous Boys 2: Lost Boys (1987)

Vampires, innocent little brothers, bad boys who aren't allowed to be bad, and victim-blaming

I am unclear on Lost Boys’ relationship with Point Break, but despite the presence of vampires in the former, they have mightily similar plots (something people on Reddit have noticed as well). Both feature a risky, bad-boy group of adrenaline seekers who seduce a himbo and bring him into their fold; both of them are notably gay-coded; both of them have a climax that involves a personality-free girl who is part of the bad boy gang and needs to be saved, and both culminate with several brutal deaths and the star himbo’s return to normal society. However, I would argue that while Point Break is surprisingly erotic, in its absurd, sunburned way, and proposes unresolved questions about the relationship between desire, freedom, and self-destruction, Lost Boys is shockingly anti-erotic, despite really good costuming and set design and a reputation as a classic vamp movie, and is a bracingly boring, teeth-chatteringly conservative eighties sex panic fest about loss of innocence which argues that the only possible sources of evil are monstrous outsiders.

Lost Boys starts, much like Totoro (1988) or Air Bud (1997), with a single parent trying to make a fresh start, moving with their progeny to a new place. As their oblivious mother job-hunts, Sam and Michael leap into the deranged fray of Santa Carla, California. The backstory here is that their mother is recently divorced and has been screwed over by whatever settlement was reached; she nevertheless has custody of both her kids, and is moving them into their grandfather’s insane taxidermy-filled house. In the opening few scenes of the movie, we get a good amount of characterization of put-upon gentle mother (Dianne Wiest), dorky and curious Sam (Corey Haim), wild but gregarious Michael (Jason Patric), and kooky, joke-loving Grandpa (Barnard Hughes). But the real opening shot of the movie is of our gang of delinquent teen vampires, the titular Lost Boys, as they pick a fight with some other delinquents on the boulevard and then maybe eat a security guard. Soon, our vampire boys meet Michael, who is bewitched by their group’s token almost-wordless pretty girl Star (Jami Gertz). Michael competes for her (sort of, since she never speaks to anyone) with vampire leader David (Kiefer Sutherland).

What makes an eighties monster movie? Well, first, lots of boys. Lost Boys has the boys; it mixes and matches its types from other feature length films with similar subject matter from the same time period, though it’s a little confused about whether it is for boys or young men; there’s cheap laughs, a put-upon single mom, a funny granddad, cheap gore, heavy gore, one sex scene, and a remarriage comedy plot. It came out two years after Michael J Fox’s 1985 Teen Wolf (not to be confused with the TV series of the same name), and, like Teen Wolf, features a gruesomely stupid and annoying white teen who struggles with the way his late adolescence transforms his body and gives him violent power.

Lost Boys’ innovation is to make dickish teen vampire victim Michael very handsome and angsty, rather than endearingly dweeby, and to make all the vampires hot too, instead of gross. They undoubtedly stole the latter part from Anne Rice, whose follow-up to Interview With the Vampire, The Vampire Lestat, came out in 1985. Instead of a goofy/gallant teen boy riding the line of childhood and awareness of the world, we get both Michael, who is older and into sex, and his younger, dweeby brother Sam , who is a teenager, but is smart, pre-sexual and a total innocent. He wears big bright shirts, has no facial hair, reads comic books, and cares about little except his dog and family.

There are also two unnerving, gruff teen vampire hunters, comically called the Frog Brothers, who are from somewhere between Monster Squad, Ghostbusters and Goonies. They too lack any relationship to sex, having dedicated their lives to eradicating vampires. The film positions them and Sam and Michael’s grandfather (spoiler) as the only things standing between Santa Carla and total destruction at the hands of the undead, which is interesting; there is no concerted force of competent experts to regulate the explosion in murder, only random kids. I do like this choice (the same one as in Girl Walks Home Alone At Night, a great vampire film), but I think the Frog Brothers also need to get a life. This obsession with ending monstrosity cannot be good for them.

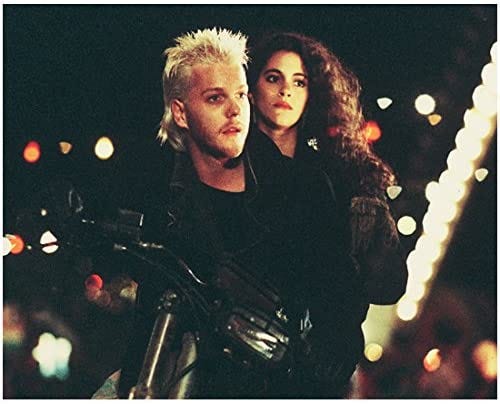

But maybe the Frog Brothers are right. I have an issue with these sexed-up vampires, which is that they lack intrigue. These vampires should be sexy-- I mean, god, look at the photo, the costuming drips with punk glamor and the kids are all cute-- but unfortunately, they lack all personality. I ignored this during my first view of the movie as a horny teenager, but it’s undeniable on a rewatch. We’re getting served Lestat-style glam rock, and a Lestat-flavored sexy boy vampire family with a leader who wants to be a dad, but there is nothing there underneath: David and his little compatriots dare Michael to eat worms, Little Rascals style, get him to drink blood, make him jump off a bridge, and then try to have him kill someone, but we don’t get any of their reasoning or interiority or backstory. I grew up on later generations of angsty sex vampires, and while Stephanie Meyer’s kinky Mormon visions of eternal families playing baseball are really not my thing, Twilight did sexual longing and meditations on immortality better! I say this as someone who became anti-Twilight while still compulsively reading it, in a similar fashion to how I would post on Tumblr about Gail Dines while still having twice weekly Grindr sex and browsing transfag Xtube porn six years later. But there is something good about Twilight that I and many other young girls recognized, which, as my 49-year-old roommate put it, “she does whatever she wants, and doesn’t care what people think about her desires.” Bella has a lot of sexual agency, and she is rewarded rather than punished for exercising it. Bella is horny, and this horniness causes her many problems, but ultimately listening to what gets her going leads both her and her quickly-aging vampire baby to a life of predestined magical bliss.

And this is the problem with Lost Boys: it does not understand that the compelling thing about a late 20th century sexual vampire is that you do really want to be eaten by him, really find his life of eternal moody engagement with blood and violence hot. You might even have someone you want to kill. Lost Boys glams up the fright fest, but they’re still convinced that the point is that your own stupid sexual lust takes you to the precipice, and then something darker and more evil outside you tips you over. Michael, despite being a bad boy pursuing a girl, is innocent as to what it’s all about until after he has already been given the deadly blood elixir, and he absolutely no-sir does not want to eat anyone. He only reluctantly falls from the bridge that the bro vampires leap from, and after he knows what’s happening to him, he’s scared; there is no question about the fact that he’d like to back out from his new destiny as a murderer. Good thing he can, as long as he kills the people who seduced him! While the bridge jump scene is kind of hot, in a stupid boy, impress-my-friends danger way, there is too much of a feeling of peer pressure and manipulation for the erotic thrill to thrive. Even as Michael’s desire is supposed to be the thing that drives this familial descent into horror, he’s way too reticent, too innocent. It lets him and his girlfriend off easy to have strangely risk-free half-vampire sex, leaving too much room for viewers to distance themselves from the monsters.

Lost Boys has some kind of heritage to locate in cult classic An American Werewolf In London (1981), too, in terms of horror and monster-masculine sexuality and camp, but I think Lost Boys has more in common with its similarly themed but totally mediocre and lifeless sequel, An American Werewolf In Paris (1997). The latter, in case you haven’t seen it, is about an evil sex cult of French wolves whi try to ruin a straight couple’s life. Like with the vamps in this movie, you can cure yourself of lycanthropy if you kill the wolf who bit you. As with this movie, our protagonist in Paris gets to be strangely innocent of his own monstrosity. Michael, our sex-hungry little himbo, goes after Star, and, because she has been seduced into a murder cult, he nearly dies. But while sexual desire is tearing their family apart, Michael seems intriguingly passive; he follows Star as if bewitched and only really begins to battle the other vampires when spurred on by his little brother. He doesn’t really have a choice, unlike other tortured Gothic heroes (The Monk by Gregory Lewis). Where American Werewolf In London has a sympathetic man half-comically menaced by his own dangerous sexuality and gory memories of his murdered friend who wants him to join him in death, whose one-night girlfriend, motivated by her own desire for him, tries to save him from himself, Paris and Lost Boys depict a simplistic war of good and evil, where wicked contaminated monsters plot to trick innocents via sex, and where those seduced have no agency, and are pure victims, pure objects of manipulation. I think the legacy of AIDS has a lot to do with this evolution in monsters (or rather, a return to Gothic horror’s xenophobic origins), and I hate it.

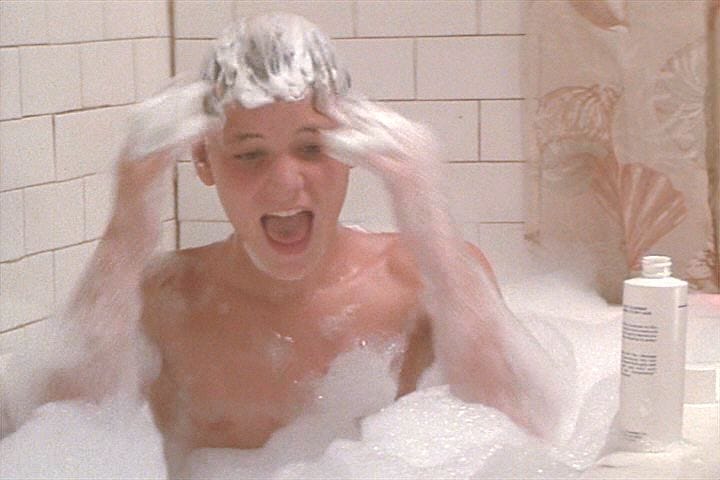

One of the most charged, interesting scenes in the film happens when Sam is taking a bath while his brother Michael finds himself waking to strange bloodlust. Michael is hungry or something, and takes a carton of milk from the fridge, but then cries out in pain, keels over to the sound of his own stuttering heartbeat, and drops the milk on the floor evocatively: lost innocence, milk carton kids, etc. Then he is overcome with the urge to murder. Sam, none the wiser and adorable, is singing a gender-playful Clarence Henry song as he bathes. “I’m a lonely girl,” he warbles, as he dips his head below water, just at the moment when Michael opens the door, presumably to attack him. Sam’s trusty Husky attacks Michael, and Sam misses the action: he emerges from the water, still innocent, wondering what happened. The usual female victim of a monster horror movie is replaced with an adolescent boy being menaced naked by his earring-sporting elder brother. I get foreshadowings of Ryan White here-- by which I mean not the teen himself, but the reaction to his death, which was used to villify gays as intentional bearers of disease/murderers and criminalize HIV transmission. The 1990 Ryan White Care Act mandated that states to certify that they had legal mechanisms to prosecute people who knowingly transmitted HIV. Later, the boys kill a vampire in the same bath, which has been filled with holy water.

Sam begins to suspect that he is in danger, but refuses to kill his brother as the local comics-nerd vampire hunters suggest; instead, he hatches a plot to rescue the relatively innocent half-vampires who have not yet killed humans and return them to human form by offing the lead vampire, to whom the vampires are now all bound by blood. The rescue mission is made more difficult by how sleepy Michael is during the day; after lifting Star and a child half-vampire out of the sunken hotel on a cliff where all the vampires live, Michael collapses like a damsel. The lead vampire ends up being not David but the man that Sam and Michael’s mother is dating. Sam and the other tweens do a home-alone style vampire kill prep session, after which they kill all the vampires. The lead vampire reveals that he was planning to seduce their mother in order to give his wild (now dead) teen vampire sons a mother figure and produce a monster family; this doesn’t make a great deal of sense, but I wonder what Stanley Cavell would have to say about this arc of torturous remarriage. In any case, when dad vampire (whose blood contaminates and animates theirs) is dead, the half-vampires become human again. Though of course that isn’t really the end, as Lost Boys: The Tribe illustrates.

As a teenager, I knew I wanted to fuck. Many teenagers do. I posted about my horniness extremely frequently online, and spoke about it frankly to my peers. I developed a dysfunctional relationship with a college student in New Jersey who would text me feet pics that he insisted weren’t flirtation, though he also signed his letters love or what you will, and a sixteen-year-old girl who told me to tie myself up and then showed my nudes to her friends; I found a boy my age who liked puppy play, though I wasn’t at all sure how to give him what he wanted. And then, around age sixteen, I met a 20-year-old who was unusually excited when I shared my interest in BDSM at a youth support group we both attended. They confessed their desire to dom me via email, I rejected them, and then, after a two-hour in-person conversation where they cried to me about how many times people had rejected them, I found I was dating them anyway. I was not, it turned out, completely opposed to it, and there were parts of the way they expressed desire for me that thrilled me. Nobody (offline) had had such a vocal and focused desire to do BDSM to me before, and I was very insecure about being desirable. I also was tired of being strung along by pen pals or trying to top my boyfriend—what I really wanted was to be dominated, fucked, hurt, and tended to. I wanted my holes filled, damn it. I wanted those things, as Bodhi would say, like acid in my mouth. I hoped that this person could give me what I wanted; the quality and power of teen lust is enormous, and transformed them in my eyes into someone sexy and appealing even though I had found the same person overbearing and off-putting before. But this didn’t last. As in our first conversation, my “no”s did not register as “no” for them, and, because I disliked conflict, I found myself pretending that I had agreed to whatever we ended up doing together, even if I hadn’t.

I do not call this person my first dom, because I never felt like the sexual play we did was a surrender or an exercise in trust; instead, I was a neurotic, usually dissociated teen canvas on which they could project their own image of themselves as an expert, when they were an inexperienced amateur who frequently underestimated how much their words or actions could hurt me. But I kept with it, for a while, though nobody was making me, because I was also invested in the fantasy of having a sexy, dangerous secret. I kept hoping I would start to enjoy the sex—that they would do something to me that I wanted. Like Michael, I lied to my parents; like Michael, I walked over a train track bridge with the person who desired me, though I didn’t fall off, and I didn’t scream. Some of those first in-person experiments with sexual pain, I sort of liked. Some I really liked (my first experience kissing someone’s feet and then being yanked up by my hair). Some of it I experienced as horrible. I found it difficult to tell my partner when I was having a bad time, because they responded to most requests I made of them by crying. Once, when I safeworded and asked them to stop biting my chest, they began to sob and then screamed at me until I found myself comforting them and apologizing. I also found myself driving them to work, saying sorry for not emailing them at least twice a day, as they commanded me to, and explaining to them (as they cried) that I would not consult them on where I went to college.

Like Michael, after I decided I needed to back out, I wanted to be innocent of the ways my own desire had been involved in my problems, because I was convinced that this desire, if acknowledged, would condemn me, and I could not figure out another way to express that I felt uncomfortable around my ex. If I had wanted to do BDSM with this person, it was my fault if I got hurt doing BDSM, right? I had access to resources that told me I was not responsible for people abusing me, but the rhetoric I most often saw about abuse online usually involved multiple back-and-forth callouts between two competing accusers; the outcome usually hinged on who litigated their own innocence and vulnerability best. When I broke up with my 20-year-old partner, a month before I turned seventeen, they persisted in calling and emailing me, trying to persuade me to ‘cuddle’ or comfort them when they were sad.

I found that I did not want to be around them socially, and so told my high school friends that they had abused me. Which I felt, even saying it, had to be a lie, even though they regularly had made me sit up anxiously waiting for an email, knowing that if I didn’t respond right away I would wake up to three to five progressively angrier emails. My best friend responded to this news ambivalently. I posted a call-out post on Tumblr where I doggedly tried to list as many wrongs as I could think of, to conclusively prove that I was an innocent victim. I omitted mention of how much I had wanted a dom and how much I still wanted to be fucked; I made it sound as if I was innocent of BDSM and had been persuaded to try it by this older person. My ex responded with a screed about how I was a liar, and had expressed interest in sex, and had wanted everything we did together. They got my boyfriend’s sister, who they were also dating, to vouch against me (small towns are weird). They pointed out that I had asked them to bite my stomach and had asked them to call me a slut and choke me. And this was true. How could I explain the ways that they had violated my consent in scenes I had consented to? My friends chose sides. And I gave up trying to ask for them to account for the ways that they had actually hurt me. It was too complicated to explain to the teens around me, or to myself.

As a child and young adult, one of the most difficult things I have had to learn is how to think about my own agency and desire. It is also difficult to distinguish between the child-me that could not have been expected to know how to communicate sexual boundaries, and the adult that must learn. I have gone back and forth many times between believing that I am responsible for all the bad things anyone has ever done to me and trying to escape that pressure through forming arguments that I am an innocent, and responsible for nothing bad or weird that has happened to me or that I have been involved in. On the one side, where I admit responsibility, I become trapped in a spiral where I give up the ability to hope that I deserve better, though I do myself the favor of recognizing my own impulses and wants. On the other side, where I say I am innocent, I have to prove that I don’t deserve the bad things that happen to me. It’s tempting to go back over the evidence, comb and re-dress the sets, to make myself look good; in the violent, depraved parts of my mind, meanwhile, I am convinced that the whole thing is a fabrication, and that I really invited each instance of sexual assault or unwanted gesture. It is hard to admit that there are multiple truths: that I may desire things that hurt me, or be responsible for things I can do to put myself in harm’s way and get myself out of it, but am not responsible for the ways people have abused their power or experience or my own vulnerability. I am still learning about how to think about this.

What I know is that Lost Boys makes a moral argument that I can’t live with: that those who are really hurt are always people who are really innocent. This line of logic insists that victims of violence or abuse must be pure. I don’t buy that; that line of logic insists that those of us who have complicated human desires, who fuck or do dangerous things to ourselves or violate rules to meet our human wants, or who make difficult choices between bad options, deserve whatever happens to us. This line of logic is pervasive, overwhelmingly so, in our culture. It was used in the 1990s to frame a teenage victim of sexual abuse, Amy Fisher, as more villainous than her abuser after he persuaded her to try to murder his wife. It has been used to criminalize HIV positive people. It has been used to get the U.S into wars and used tojustifyAmerican and Israeli drone strikes targeting civilians. Twitter threads argue that Texans without power, many of whom are working poor, deserve to freeze to death because many Texans voted Republican and are racist, and gays insist that people who party on Fire Island deserve to die of COVID.

I like horror because it reflects cultural anxieties, and I shouldn’t be surprised it’s reactionary. But Lost Boys still disappoints me, because it refuses to engage with an upsetting question: what if we aren’t innocent? What if we do want??