imaginary teen girls 1: trans desistance, tummy holes, and Arkansas

The bills passing this week in Arkansas, Alabama and elsewhere have a direct relationship to the figure of the innocent teen girl created by anti-trans journalists over the last few years.

Lots happened this week. Derek Chauvin is on trial for the murder of George Floyd, in which the prosecution is showing the nine-minute video of him kneeling on Floyd’s neck while an EMT begs him to check Floyd’s pulse. The defense argues that George Floyd, the murder victim, might have done drugs at some point. No matter whether or not Chauvin is found guilty or sentenced to serve time in prison, the lack of closure and renewed threats to safety his trial brings up for people harmed by police officers wielding their power with impunity to hurt Black americans and other marginalized people promises to be catastrophic (use of force and human rights abuses skyrocketed in Rikers Island in New York during the pandemic). These trials always turn on whether the victim ever did anything to deserve state violence and assume that the Black victim, rather than the armed white perpetrator, is guilty; they are a farce of a judicial system which barely pretends not to endorse white supremacy and genocide policy. This trial and its results, whether they let a cop free after a horrific murder or condemn him to prison alongside hundreds of thousands of people denied freedom, will not see the end of the fight against racism in the U.S. or end the Defund movement.

Meanwhile, the legislature of Arkansas passed not one but three bills into law that, respectively, protect medical providers who refuse any type of health care to LGBT people,bar trans girls from being on girls’ sports teams, and ban healthcare providers from offering transition-related healthcare such as puberty blockers and hormones to teenagers.

While the latter bill has not yet been signed into law (though the Governor, Asa Hutchinson, is unlikely to veto), its passage through the legislature has resulted in a sudden, fixated concern about Arkansas on the part of many trans people around the U.S and their friends. Trans care is already inaccessible and expensive for young people, and teens can be prevented from accessing it by their remoteness from healthcare providers or lack of parental consent. An official legal blockade closes options further; teens who want hormone therapy or puberty blockers must travel to other states; doctors who try to refer patients elsewhere are potentially subject to legal action. Chase Strangio, a lawyer who is among the most outspoken about the legal threats to transgender bodily autonomy, has been publishing updates on the status of other bills and encouraging people to donate to nonprofits that support LGBT youth in Arkansas. Trans youth have spoken out against the bill and others like it.

In the wake of this bill, I encourage people to support organizations like Intransitive, which redistributes money to trans people in need in Arkansas. You can find more resources for transgender people in Arkansas here.

All of these bills, in my opinion, are written with both the goal of legislating visibly trans people out of existence (and out of safety) and with the objective of protecting an imaginary white innocent girlhood.

Notably silent on this and other bills across the country (in Alabama, Michigan, South Carolina…) is one Jesse Singal. To be precise, he condemned the bill in a post last year and then tweeted about it once after its passage to say it is bad. Which is interesting, since the Alabama bill he says is “bad” seems to paraphrase an article he published in 2018.

The bill, HB 1570, states:

“(3) For the small percentage of children who are gender

nonconforming or experience distress at identifying with their biological

sex, studies consistently demonstrate that the majority come to identify with

their biological sex in adolescence or adulthood, thereby rendering most

physiological interventions unnecessary.” (Section 2, paragraph 3).

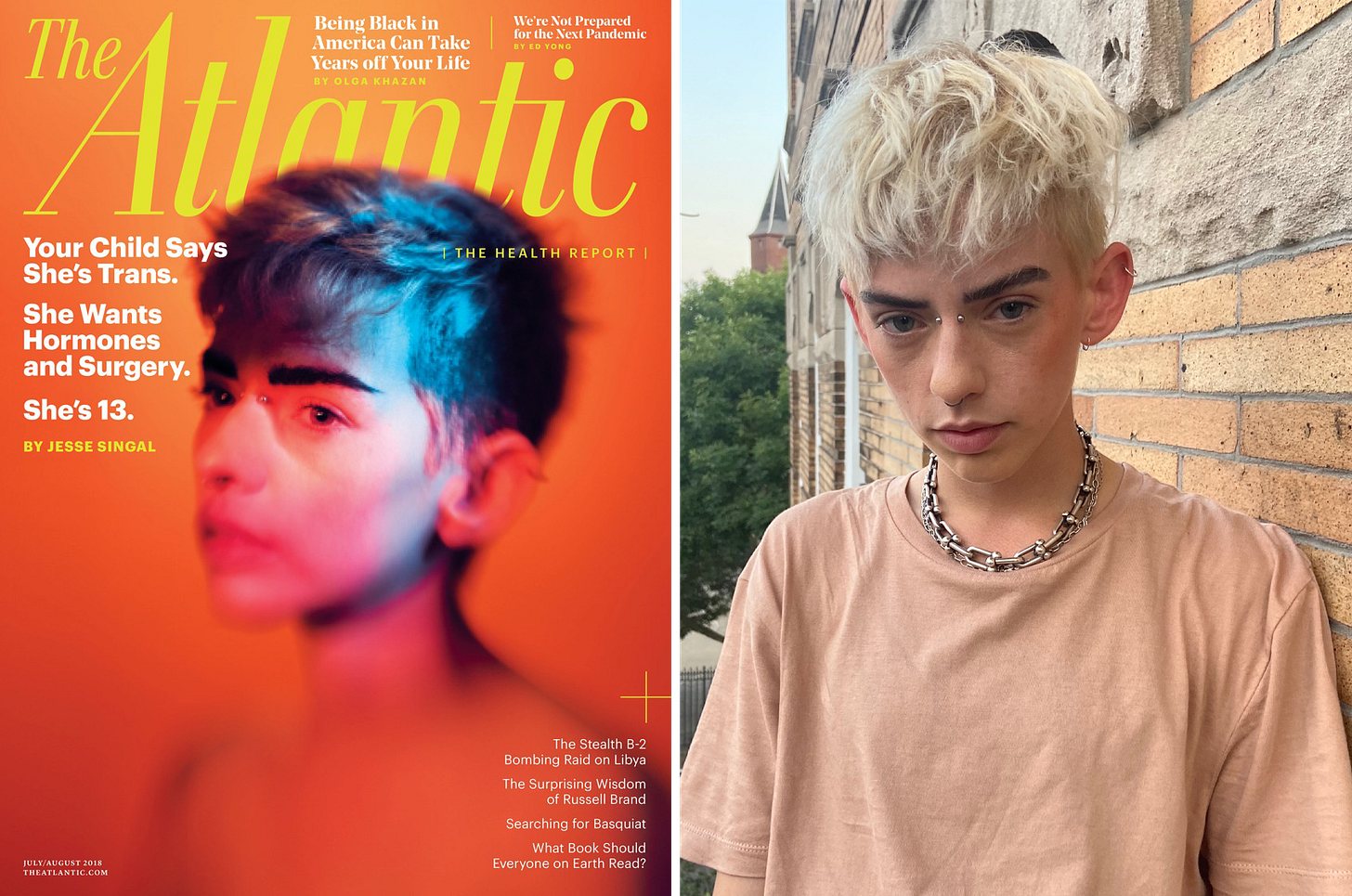

If you’re not clear on exactly what I’m talking about with the Singal piece, let me congratulate you. When Singal’s article-- When Children Say They’re Trans-- appeared in The Atlantic was published in 2018, I managed to avoid it for all of two weeks before a cis person sent it to me with the caption “Read this and thought it was interesting. Thoughts?”

The article opens with a picture of an adult trans person, Mina Brewer, whose photograph was used without his permission. It opens with the decidedly creepy sentences “Claire is a 14-year-old girl with short auburn hair and a broad smile. She lives outside Philadelphia with her mother and father, both professional scientists.” Readers may be forgiven for assuming that Claire is the person shown on the cover. The start of the story, narrated by “Claire” and parents over an evening spent with Singal, describes how Claire believed she was trans, but then told her parents, and then was persuaded not to transition. The fact that, at 14, Claire has no ability to pursue transition without parental consent--was in fact unable to even articulate a new gender without significant, and at least temporarily successful, parental intervention to make sure Claire continued to live as a girl-- doesn’t dissuade Singal from using the rest of the article to whip up a frenzy about the possibly horrible consequences of affirming health care for trans children. Claire was misled, he opines; Claire was sucked in by that oh-so-seductive trans online ideology, which persuaded Claire that the discomfort she felt in her body and life was dysphoria. Thank goodness she was wrong, and is a girl (and parentally supervised in her interview with a journalist)! But other children may not be so lucky.

He cites statistics that indicate the number of self-identifying trans people has doubled in the last decade or so. He makes sure we know that he’s okay with trans people in general, except for the ones who aren’t really trans and are going to regret it later, who might be any of us. He points to trans Youtubers, whose videos are fed “by algorithm” to young children. And he appears to feel an urgent dread that, somewhere, 14-year-olds are receiving permanent, life-altering medical treatments.

Where, exactly? Which treatments? Well, Jesse says “it’s now more common for 15- and 14-year-olds, and sometimes even younger kids, to begin hormone therapy,” though he does not cite his sources or speak to anyone who has prescribed hormones to children in this age range to ask about details on what hormone regimens for this age look like (as someone who began HRT at 15 on a dose somewhere around 20% of what’s prescribed to adults-- 10ml of 200 mg/ml depotestosterone weekly, where most adults are at 50ml or more-- I saw almost no physical changes for three years, until I upped my dose). His examples of reckless care fall flat: he names a transgender health site that --gasp-- “encourages parents to seek the guidance of a gender specialist” and complains that GLAAD’s website has too many articles about supporting trans children and not enough about parents engaging in diagnostic assessment of their children’s dysphoria.

In the middle of all this, Singal says:

“A small group of studies has been interpreted as showing that the majority of children who experience gender dysphoria eventually stop experiencing it and come to identify as cisgender adults. (In these studies, children who suffer intense dysphoria over an extended period of time, especially into adolescence, are more likely to identify as trans in the long run.).”

Which is similar to the language in the HB 1570 bill, albeit with a couple of caveats.

Jesse would be quick to tell you that this article is from three years ago, and note all the things I’ve omitted here. For example, he immediately follows his suggestion of widespread desistance up with noting that these studies have been critiqued on methodological grounds. He runs up his wordcount with assurances that he understands the stakes of denying trans people health care, and describes how informed-consent practices have radically improved mental health outcomes for adults.

But then he segues into an interview with a detransitioned woman named Max, who had a double mastectomy as part of a transition she now thinks was the product of internalized misogyny and trauma (fair enough). Max, who began identifying as trans in high school, describes how she badgered reluctant parents, talked to a therapist who suggested she might not be trans, and consulted an endocrinologist, who was reticent to give her hormones, but eventually persuaded the doctor to prescribe HRT and perform surgery. Despite Max’s agency in her own narrative, the many gatekeepers in her way, and the absence of any apparent external coercion in her description of the relatively long-term period where she pursued transition, Singal implies that forces external to Max worked in invisible, dastardly ways upon her to persuade her to transition, and ultimately marred her body.

What are we to do about this? Well, since Jesse says he doesn’t endorse banning healthcare for trans youth, it seems we are mainly supposed to worry. Not to imply that Singal wants to close off access to care--not at all! But what if others desist from transition? How awful! Singal includes a picture of Max, who is fat, wears men’s clothes, and has facial hair that she appears to be growing out. The image caption notes that testosterone caused this hair. The fact Max’s beard could be shaved, if Max wanted, or removed with electrolysis, if this was important to Max, is not noted. While Max obviously has the right to not be asked about her beard, this lack of context probably implied to some readers that daughters everywhere may be stuck with inexplicably irremovable undesired beards--instead of settling, as Max appears to have done, into a new kind of elective gender nonconformity, in which, in my opinion, she does share a lot of material stakes with trans people who are punished for looking gender nonconforming. Singal then closes by quoting a host of other detransitioners, who are accompanied by portraits (no photos of trans people who are doing okay are featured, except for that wordless picture of Mina Brewer). Assumed from the start is that it would be really awful for a child to be trans, because it makes you ugly or scarred, so if it could be ruled out, that would really be best. The Atlantic ended up needing a follow-up piece because many trans people, like me, were upset about all this.

I had my own correspondence with Jesse Singal back in 2016; you can see screenshots on my twitter. I engaged with him about an article called “What’s Missing From The Conversation About Trans Kids.” At the time, I was disturbed by his preoccupation with breasts: when I brought up teen transitioners’ ability to account for our own bodies and decide what to do with them, he noted that he’s met with women who regret losing their breasts. In one email to me on July 31 2016, he said:

“In very limited searching, I've already found multiple women who have gone through nightmares because we can't have a complicated decision about this. In both cases, they had severe mental illness as adolescents, and in both cases that illness brought with it dysphoria. They were told that if they were dysphoric, that must mean they're trans, and they both got double mastectomies. A year or three later, they realized that all along they were lesbians, and both have since detransitioned. “

Besides the “multiple” being collapsed to “two” here over the course of this paragraph, and the implication that mental illness precludes the possibility of being trans, I do take issue with the phrase “nightmares”. What’s the nightmare-- to have a transsexual body? To have it while not professing a clear identification as a transsexual? But the other part is the allocation of agency. The women “were told” that their dysphoria made them trans, and that this necessitated surgery, Singal says—which invokes a vision of two catatonic figures being let blithely along to the surgical chopping block. But who told them? And—it’s worth noting this— there is no diagnostic guide, in the U.S or elsewhere, that mandates top surgery as a condition of FTM transition. Top surgery is pretty hard to get, in fact, with psych appointments, letters, and attendant financial and insurance woes that can take months or years to navigate, depending on someone’s age, savviness and location. There are often problems of agency in top surgery— for example, my surgeon persuaded me that my nipples should be much larger than I originally wanted them to be; someone else I know decided that they didn’t want nipples after all at the last minute, and the surgeon wouldn’t do it. But the problem is rarely that anyone is forced to get surgery in the first place. I had to campaign for years for my parents to support such a surgery, and they had to then drive me around to psychiatrists who asked leading questions for months before I was allowed to do it.

Agency doesn’t mean our decisions about our own bodies always work for us. Often, they don’t. There are lots of people I know who have “detransitioned” or retransitioned and live as lesbians or gay men, with or without breasts, with or without beards. I think they all have a variety of feelings about their bodies, good and bad, as do the trans people, myself included, who have chosen specific regimens of hormones or surgery for ourselves. Many people, cis and trans, live without breasts after having once had them, and while the relationship to the loss of one’s breasts varies and can definitely be traumatic, two people’s experience of trauma and regret after voluntary mastectomy doesn’t delegitimize others’ choices about their own bodies-- to choose, to change, to choose again. It is interesting, in fact, how little people’s choices about their own bodies mean for other people’s choices about their own bodies. In any case, there is nothing repulsive about a trans body. Earnest little 20-year-old-me said so. Jesse replied:

“are you really going to argue there isn't something horrifying about having an elective mastectomy and then regretting it? It sounds pretty horrifying to me…”

and

“If we can't agree that unnecessary major surgery, performed as a psychological intervention, which removes organs used by the vast majority of women to breastfeed, as a source of pleasure during sex, or both, is horrifying, then we may be too far apart on this stuff.”

While I appreciate Singal’s concern for my former breasts (or organs) and the breasts/organs of others, this exchange distilled for me what the root of all this really is for Singal-- a preoccupation with preserving the fertility and sexual availability of people he thinks are, or might be, or might have been, young women.

It should be noted at this point that women lose their breasts to breast cancer far more often than they lose them to a transition they later regret-- more than 100,000 women undergo some form of mastectomy a year. But Jesse Singal is not, as far as I can tell, interested in protecting women from breast cancer or investigating, for instance, the racism endemic in preventative care that means far more women than necessary develop cancers that could have been caught early. He is fixated on the horror he feels about a lovely, fertile young girl choosing to lose her healthy breasts. This appears to explain why he leaves trans girls--and the violence, misogyny, and sexual abuse they often face, particularly in reaction to their bodies-- completely out of his complex trans equations of risk and damage when families assess how to support trans kids. His questions are not about preventing harm or abuse, but trying, at any cost, to preserve would-be deserters’ relationship to cis womanhood and fertility. He can’t stop the adults, but if he can stop the girls, perhaps some titty can be spared.

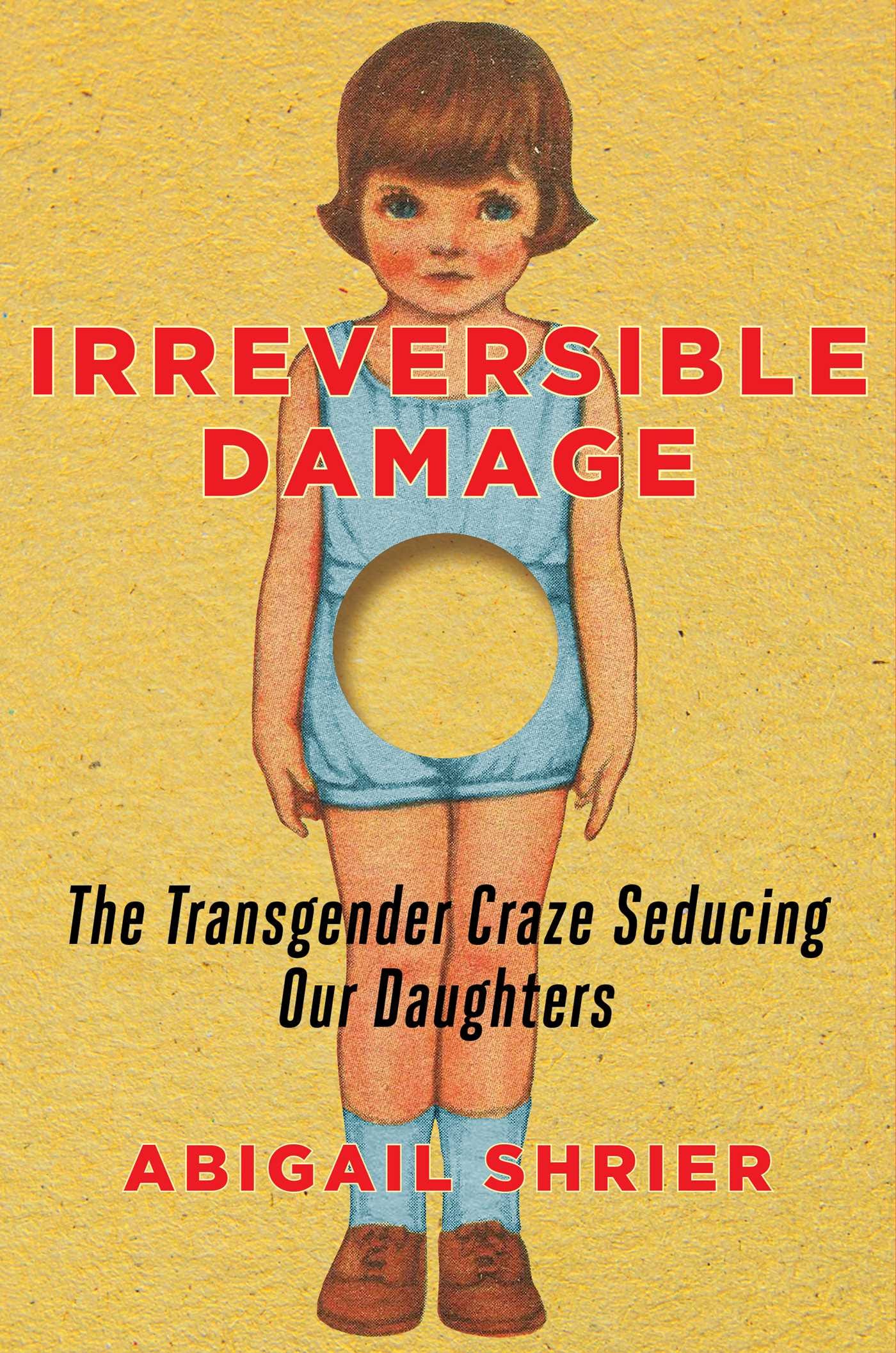

This is also the subject of concern for his friend Abigail Shrier. In Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters (hot!), which famously features a little girl (who looks about four or five) with a hole in her tummy on the cover, Shrier too panics about the idea of teen transitioners going wild and “young girls” being seduced by gender ideology. But she only is interested in trans boys. The book opens with a quote from a Billy Joel song: “she hides like a child/but she’s always a woman to me.” The irreversible damage--the tummy hole-- that Shrier is so worried about is implicitly hysterectomy, but she considers other things equally scary, like having trans friends on Deviantart, or cutting off contact with the parents that tried to stop you from going to GSA meetings. Shrier and Singal both seem to believe that transmasculine teenagers who come out after appearing to be regular little girls cannot be boys. But Shrier takes it a step further-- they also cannot be adults. “This book is not about transgender adults,” Shrier says in her introduction “The Contagion”, though she claims to have interviewed “many.” But Shrier proceeds to describe a host of college-age transmasculine people who access hormones and surgery after exiting their minority. These people, for Shrier, still count as “young girls”/”our daughters”. For example, “Lucy”:

Shrier pays lip service to the idea that trans people can in fact really need to transition, but, as she interviews the parents of various trans adults who have severed ties with transphobic families, she seems deeply invested in the idea that no teenage “girl” could possibly know enough about themselves to make decisions about their own body--and after they exit teendom, they still remain rendered in Shrier’s text as permanent children, albeit luscious ones. Shrier relies heavily on parental descriptions of lost daughters as sexy (“she was a developing body, wearing a bikini at the pool”, one parent reminisces about her estranged son), and compares their freaky teendom to her own wholesome kiss with Joel from Jewish day school. Nowadays, Shrier implies, the girls just don’t develop like they used to. “Julie,” a trans teen, becomes “angry, detached and cocky” after meeting with a gender therapist. This may have something to do with “Julie’s” parents deciding, after “a couple of days or a week,” not to use Julie’s preferred name and pronouns any more, but whatever. Later, Julie’s mother implies that Julie being unable to compete with male dancers after changing gendered ballet classes is evidence that Julie’s transition will hurt not only his body and his career, but others’ too (shoutout to “Julie,” who survived these emotionally manipulative abuse tactics-- and congrats on getting out).

There’s a really big question here for me. Who is the seducer of the world’s Lucys and Julies, in this story of the tiny girl with the hole in her tummy who has cut off contact with her family after college? It seems like it’s probably trans people, with a few dumb, abetting doctors-- though as Shrier pushes forward, it seems like every potential trans person collapses, a hollow illusion masking a “real” little girl. But this doesn’t make sense. For there to be a transgender craze, there must be the crazed. At some point trans men must make the jump from seduced little lamb to wicked/irresponsible online parasocial groomer, must we not? There would be enough evidence that we fuck our own to make a case that our motive for seducing girls into manhood is to have sex with the resulting men. But maybe this kind of rhetoric complicates Shrier and Singal’s assertions too much. For one, that would imply that they recognized trans people having sex with each other at all. It also doesn’t work since it implies that the transitioning teens themselves may one day have the same kind of agency as their seducers, which Shrier and Singal just can’t admit. Trans women like Grace Lavery, meanwhile, are routinely targeted with allegations that they are grooming any younger people they interact with. So maybe they’re all supposed to be the ones seducing us. Just sort of behind the scenes, directing, as it were, trans men’s social time with one another. And what horrible things await if this continues?

“The cost of so much youthful indiscretion is not a piercing or tattoo,” Shrier says. “It’s closer to a pound of flesh.” By this, she means “lifelong hormone dependency” (people can and frequently do stop HRT; they are only dependent on exogenous hormones if they’ve removed both ovaries or testes, which many people choose not to do-- though some states once mandated sterilization as a condition of receiving HRT) and “disfiguring surgeries” (while I’d like to say this is hyperbolic, love the bodies of trans people, and admit there are amazing surgeons out there, it’s true that many surgeons are in fact less competent than we would like--which is a result of a broad lack of access to medical care and education for doctors). But never mind the elective and lengthy process trans people need to go through to access care. Any amount of access is too much-- a hole right through the tummy.

Jesse Singal has said relatively little, so far, about his supposedly negative position on the Arkansas and Alabama bills which would seem to do much to prevent the kind of mistaken transition he is so up in arms about. He says he is against this wholesale ban, that his own recommendations promote only caution and careful questions, but he spends more time decrying critiques of binary sex assignments than asking his supporters to speak out in favor of continued trans access to health care. I should be fair to him, since he’s busy with other important things-- he spends a little time complaining about anti-bias training in schools, and a little time complaining about cancel culture in YA literature, a market he neither writes for or reads. Shrier, meanwhile, testified against the Equality Act, citing the probability that a spate of trans girls entering sports en masse would crowd out delicate natal females who can’t possibly compete (a great message for young cis women athletes, to be sure).

But you know who did have something to say about the Arkansas legislation? Elliott Page. Elliott Page, bless, has shown up several times on Twitter or in brief interviews to defend trans children’s rights since his coming out last year. He seems to prefer keeping his own story out of the spotlight, instead generating a platform as a benign figure of delight for other trans people and occasionally promoting causes in our name. His TIME magazine cover story features a cute outfit, but most of the text actually focuses on broad transgender rights in America. Page gives only the barest, most basic details about his own transition and haircut, as is his right. A question for me is what Page’s career will look like in the future— I desperately want him to play men onscreen and to develop as an actor beyond his long-typecast role as lost teen, or former teen.

Which brings me to the actual introduction of this intended series of posts: to think about the ways teen girls are and have been rendered as both young people with significant agency and as virginal children who embody other people’s expectations for their heterosexual futures--and who are the subjects of horrific violence. Elliott Page is and has been a man, but his early roles were all about plumbing the questions of teen girlhood and the violence committed against/the problems of agency concerning teen girls--and at every turn, he encounters tropes about what it means to be seen as a young woman. His filmography through the early 2000s saw him develop new versions of old tropes. Page’s teens are innocent, cute, and small, but also unconventional, offbeat, wry, brimming with both certain innocence and also enormous capacity for precocity, depth, humor and sharp insight; they pursue what they want, suffer indignity, and get their own back. Page, a teenager himself at the time of his early work, saw his own body reimagined as a place to project fantasies and fears about teen girls--most vividly in An American Crime, in which he plays Sylvia Likens, a girl physically abused and killed by her female caregiver. In Hard Candy, he delivers a fascinating, deeply enjoyable performance as a likable and totally opaque tomboy pedophile-killer who is repeatedly almost the victim of horrible violence but consistently turns the tables on her would-be assailant; in Juno, he created an iconic character whose casual sexual agency and pleasure combines with a sympathetic picture of a young person resisting inappropriate sexual attention and being supported to make difficult decisions by caring but bumbling adults. Page’s work with the figure of the teen girl changed how some films depicted girlhood, though his control over narratives was limited. His filmography also intersects with a host of contemporary films about victimized girls, frightened girls, evil girls, sexy girls, all dealing with the twin threats of sexual abuse or assault and the promise of personal agency-- Jennifer’s Body,Ginger Snaps, Easy A, Mean Girls, or, a little later, Stoker. And his films also inherited a legacy of the teen girls in movies to come before-- the Molly Ringwalds, Sarah Baileys, and Dolores Hazes.

Elliott’s specific work in relation to his gender and the idea of the teen girl has already been the subject of this great piece of writing by Annie Rose Malamet; I will reference but try to not repeat Malamet’s work. My goal is to watch Page’s movies in context with some others from the same period, and look at the shifting agency, sexual and otherwise, of teen girls in early 2000s movies, what their innocence seems to signify, the fear they inspire. What does the perpetual innocence of teen girlhood mean for their personhood? Once innocence vanishes, is their personhood gone too? Does it take violence to preserve teen innocence? Is it violent when it ends? Under what circumstances does a teen girl become a monster?

Stay tuned! My first stop will be to look at teen girls as killers in Hard Candy, Stoker,Teeth, and Jennifer’s Body.

note: In related news, many people have called for creators to leave Substack as a result of them giving some money to Jesse Singal. I am considering options for moving to a different newsletter or Medium platform for future writing in the coming months, though, as I am not giving or receiving money from Substack, I don’t know if Substack particularly cares. If you have suggestions for a forum to post/distribute essays like these, please let me know!

thank you, Hal. very insightful and vulnerable. <3