Seduction, Corruption, Desire Part I: One, Two, Three (1961)

Cold War America wants other people to be masochists, and James Cagney is hot

[Video: She Married a Communist?]

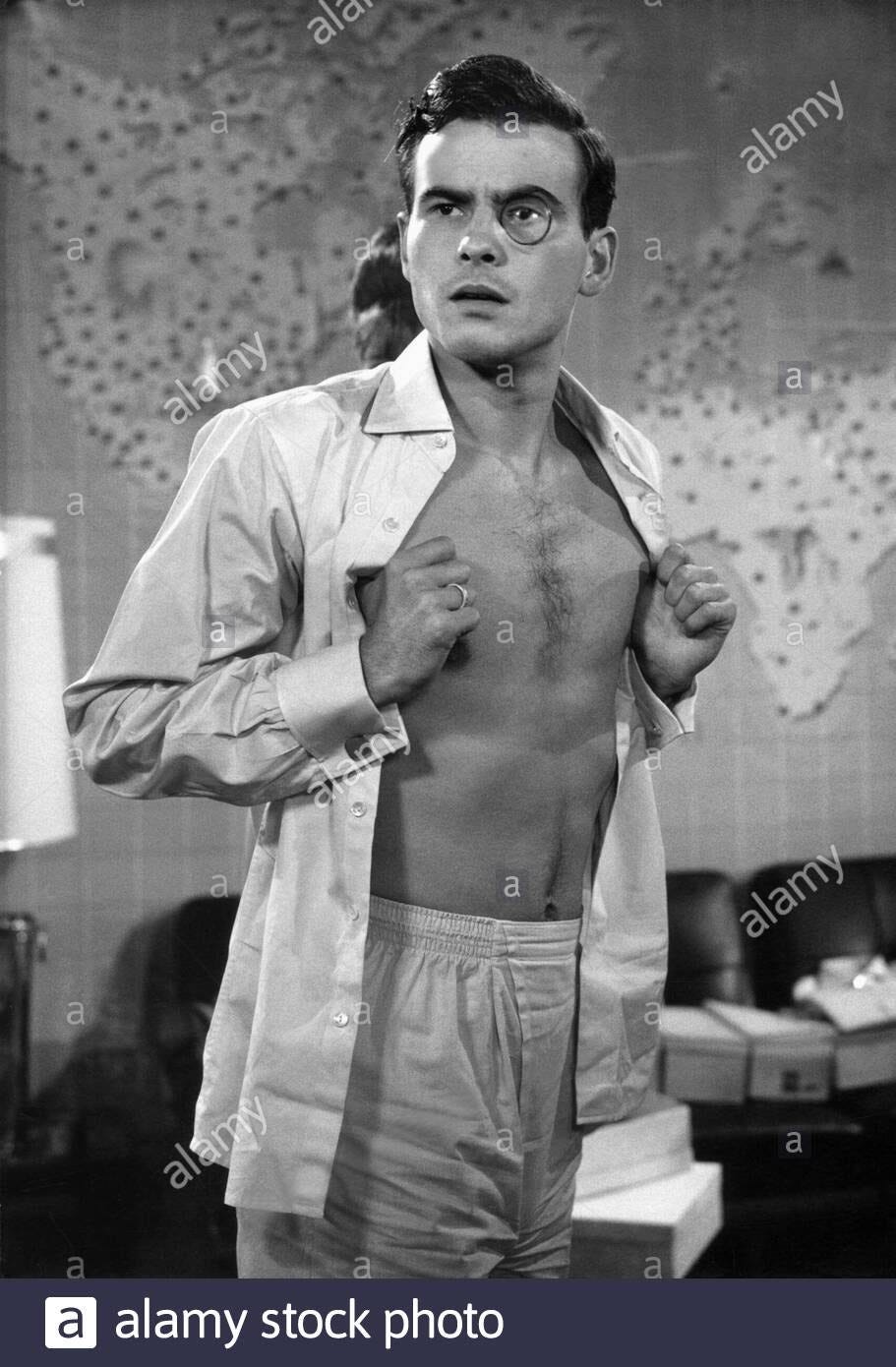

Otto the Communist (Horst Bucholz) is an idealistic, handsome scientist who wears no underwear. At the start of Billy Wilder’s One Two Three (1961), he’s just a regular Soviet guy with a motorbike. He meets a rich girl while he’s carrying a poster of Kruschev, and she falls in love with him because he calls her a typical bourgeois parasite. By the end of the movie, he has been transformed into a person unrecognizable to himself by his own desire, state violence, and the self-serving, sadistic impulses of a soda executive.

I first watched One Two Three in college, in a Film and Twentieth Century Europe class at the University of Washington. The lecture we watched it in was about post-war Germany and the sudden omnipresence of American troops, companies, and factories in a state divided between Communism and Western Democracy. During the period I watched it, I was absorbed in torment over the conflict I imagined existed between my 18-year-old-self’s masochistic desires and my then-politic around porn and BDSM. On the one hand, there was the anti-porn tracts I had read on Tumblr arguing that participating in consumption of porn or sexual content with themes of violence contributed to the inarguable epidemic of violence against women. Evidence that the straight porn industry involves horrendous labor abuses were paired with assertions that to consume any porn is evil; this made me afraid of even sex-worker-run alternatives, and certainly of my own masochism. Though-- I did indulge in the superb masochism of adopting a belief system that required me to adopt a constant state of guilt for the source of my own pleasure. On the other hand, there were pro-sex-work books and blogs I had also read, arguing that sexual violence did not need porn to exist, and that while sexuality in the world is related to power dynamics that harm people, and media can help reproduce/affirm power relations, the relationship between porn and rape is not causal. But I was persuaded, ultimately, by desire. Before the end of the year, I would fling myself into the arms of an older dom who was having his own moral crisis about fucking an eighteen-year-old. I would also start a pattern--very normal, I am told-- of being very loud about my values and then realizing I had quite different ones. I remember that the first time I watched One, Two, Three, the thing that excited me about it and unsettled me was the degree to which it showed a moral landscape in flux.

[Video Clip: Scarlett Loves Otto]

Otto seems to know what he wants--a simple Soviet life with a good Communist wife. But then he falls for sweet, hot-blooded air-headed cola heiress Scarlett-- who is not only a bourgeois parasite but does not, it seems, really understand what exactly his politics or values are (“he’s not a communist, he’s a Republican,” she says, “he’s from the Republic of East Germany.”). Why would he fall for her if he is so wedded to his beliefs? His next dubious move is crossing the border into West Germany to tell her father’s subordinate, C.R Macnamara, that he’s married her, opening himself up to sabotage by the grim, pint-sized CEO of Coca Cola Berlin. Macnamara (James Cagney) hatches a plan to put Otto in jail before word of his virile ideology gets to Mr. Hazeltine and costs Macnamara his job. But then he discovers that Scarlett’s already schwanger. Macnamara plants an Uncle Sam cuckoo clock on Otto’s motorcycle, forcing Otto to be tortured, which in turn makes him falsely confess to being an American spy. Otto is sent packing for the West, where he is recreated by Macnamara My Fair Lady-style as an aristocratic businessman so that Macnamara’s boss won’t be so upset about Otto and Scarlett’s baby. It works; irony of ironies, Otto is promoted above Macnamara on the spot. The final gag is how perfectly Otto succeeds at becoming the embodiment of everything he supposedly opposes, Prole turned parasite, anti-imperialist turned imperial dandy.

Otto is hard-bodied and motorcycle-mounted-- but in his initial straw-man wide-eyed Communist anger, he’s nearly as innocent as Scarlett, regurgitating party lines and unable to adequately defend his principles in dialogue. When he’s eventually dressed up like a pet for Scarlett’s parents, he evinces distress, but not resistance; he parrots the lines fed to him to impress her white racist Southen father. At this point, of course, he’s in a hole-- he can’t go back to where he came from, because they already believe he’s with the enemy. Otto’s helplessness is why this film was allowed to be screened, I think, despite its critiques of capitalism. The only Communists we see besides Otto are fat oligarchs trying to get Coke’s secret recipe out of Macnamara, and they in their turn are easily bamboozled by a sexy secretary into making major concessions. Ultimately, the film argues, Americans do bad things, but everyone with a critique of us is either worse or as stupid as a child. Like Sade’s Justine-- except rather than a virginal girl cast out of a convent, the virgin here is Soviet Otto, misused by his own authoritarian state despite his earnest belief and flung defenseless by his own desire into a capitalist society that will eat him alive or assimilate him. His sex appeal is part of the schtick. I like watching James Cagney supervise the undressing of Horst Bucholz’s nubile young body.

I don’t know if you’ve ever made the mistake of falling for someone with the knowledge that they could destroy you, or at least change you in a way that is deeply painful. I’ve done this many times. Raised by other depressed queer teenagers on Tumblr, I have a habit of responding to others’ personal crisis as if it is an act of flirtation, an invitation to be saved or made new. The more extreme the crisis (PTSD, a recent abusive relationship, alcoholism, a manic episode) the deeper I dive. Usually this is a bad experience for everyone involved. When I was a teenager, there was a naive earnest, wholesome energy in this kind of doomed project-- I genuinely believe in the transforming and healing power of love and care. But there’s also a dark, self-serving delusion that I have been aware of for many years: if I succeed in saving someone from the edge of the abyss, the little abandonment-phobic goblin at the back of my brain insists, they will have to give me love forever. As you might imagine, this rarely ends well; if you try to save someone whose problems you are not equipped to handle, they just end up hating you, or else imagining that they depend on you to function and you owe them perpetual care--both of which are unsustainable. But I have to admit that something deep within me has often thrilled at the fixated attention that accompanies the hatred/desperate gratitude of someone I am trying to forcibly rescue. I have often pretended it signals something like the beginning of an enduring love-- and indeed, if I persisted, I might be able to convince someone that they need me in order to understand the world, or be happy, though this would put me in the position of admitting that there are limits to what I can actually provide. Is this also what’s happening for Otto with Scarlett, or to Macnamara with Otto?

Macnamara is shown being dismissive and neglectful of his own wife and snotty biological children, until the end, where he races after them to try to reclaim them when they try to leave. Meanwhile, his control over Otto’s new persona bespeaks a giving-birth-to that, while shown as prompted by selfishness, is so meticulous and personally attentive that it reads as obsession. The inevitable Cold War propaganda here is that, to quote Meryl Streep in Devil Wears Prada, everyone wants to be us, though we hate ourselves and hurt our own. Is this really true? We certainly need it to be, to justify imperial acquisition and paternalism. Macnamara, like Miranda Priestly with Andy, needs Otto to want to be a capitalist, because it will forever put Otto in his debt. Otto will belong to him. And the film seems to validate that post-torture Otto, unlike prim goody-two-shoes Andy Sacks, does, in fact, really want this outcome. Otto may pretend disgust or horror, but really, this film insists, he wants what ultimately happens to him-- he wants to be consumed. Of course, Otto at the end of the movie has some power, wed as he is to a rich young lady and bestowed with a high-paying job. This is the seduction of capital: it’s nice if you have the power. What would happen if he had no power at all?

[video clip: “Come on, let’s get going!”]

Otto’s descent, with MacNamara as his capitalist Screwtape, echoes an earlier transformation we only learn about in odd lines of dialogue. This is the shift of Macnamara’s secretary Schlemmer from Nazi to stooge--and pain toy-- of Western democratic capitalism. Schlemmer-- a Bill Nye lookalike, long-limbed and bespectacled-- is an ex-Nazi who is in one sense Otto’s future, living in an assumed identity that Macnamara could topple at any time.

Schlemmer and Macnamara have some kind of d/s thing going; Schlemmer jumps, clicks his heels, dresses in drag for aforementioned oligarchs, and bows to all of Macnamara’s commands. He owes Macnamara his rescue; now he, and all of West Germany, are Macnamara’s bitch forever. In two playful scenes, Macnamara asks Schlemmer what he did during the war. The first time, Schlemmer answers that he was never in the S.S; the second time, he responds that he was a pastry chef, and was also literally underground during the entire war, and so had no idea what was going on. We, of course, know different. Ha-ha. Used to accepting authoritarian commands without question and doing evil for no real reason, Schlemmer adapts to Western Democracy’s equally authoritarian and exploitative relationship to his labor, and seems to take pleasure in being abused. Macnamara assimilates Schlemmer, allowing him to become part of the postwar social world, bringing him into the fold-- though exposing him to plenty of harm along the way, in a kind of sadistic comeuppance designed to make American audiences feel good about our response to war crimes even as our politicians--Nixonian Macnamara lookalikes-- prepared to entomb Vietnam and Cambodia in napalm. I like the little zing of self-critique in this tableau, however shallow: the film acknowledges that the legacies of spiritual weddings between capitalist democracy and fascism are still with us. I do think One, Two, Three’s insight into Schlemmer’s seduction is sharp. It’s contemporary enough at the time of its making that it manages to catch culture in the act of generating the forgetting of harm, even as it argues that the person facilitating this is a comedic hero.

Watching One Two Three, I was struck by just how hot James Cagney is as C.R Macnamara. Was I aware of this the first time I watched the film in college? He’s short and loud, insistent and clever, and has a sort of wry, square-jawed, pragmatic capability. While he’s absolutely a chauvinist and a self-serving, greedy schmuck, his patter is resoundingly satisfying, nearly hypnotizing.

Do I love tyrants? Don’t answer that. I do like to be told what to do. On a personal level, Cagney’s height and stocky figure and expressive face are deeply physically attractive to me. I think I have a thing for guys who look like they could tell me where the best deli is if I was Frank O’Hara on his lunch hour in 1959. He inspires confidence because he knows what’s up. Do I want to belong to him forever? Only, I suppose, if I have a little control over the terms. Which is exactly what nobody, in dealings with postwar America/Macnamara is allowed to have. If you give in at all, you give everything-- and you find yourself in a new world that’s ruled by dollar signs, and soda. And you must give in: in this world, there are no other options. Even his wife and kids can’t escape him, even as he rules their lives while paying them little personal attention. We may be bad, but we are the only choice.

I think many (Western, white, at least) leftists and communists in 2020 secretly or not-so-secretly wish to believe we are doomed to lose, that we are struggling hopelessly against an enemy greater than we could hope to defeat--even as we also see, repeatedly, that when striking workers reclaim property or destroy police stations, people do make governments and autocrats and oligarchs shake in their boots. One, Two, Three is part of the cultural landscape that makes us unable to imagine alternatives to defeat-- it’s a smart film that wants us just to give in, to stop fighting. It does make its argument appealingly transparent, which to me means I can watch it with pleasure, and even find something delicious in its seduction. Sometimes I want to be helpless against power, to have no agency to choose good or evil, or to differentiate between options-- to have one choice only, and be forced to love someone whose attitude toward me ranges from hatred to casual neglect.